Armenia

Part 2

Monday 3 July: Dilizan-Yerevan-Sevan: 108 km: 1 pass

Oh surprise! The sky is covered this morning, but the temperature is mild in spite of the wooded mountain. We leave Dilizan (alt. 1300 m), this peaceful harbor, by starting the long climb (15 km) of Sevan Pass (alt. 2114 m) across forested areas of pine and fir. At the summit, the clouds have disappeared, making place for a radiant sun. The view to Lake Sevan with its turquoise water is breathtaking. We descend to the edge of one of the largest high-mountain lakes in the world. This vast sheet of fresh water is suspended at 1918 meters altitude. We follow it for awhile, then speed toward Erevan (the capital) via the country's only autoroute, separated by a wide sidewalk, a true roller coaster approximately 50 km long, which is not nothing, but with a tail wind we can raise the large sail.

We approach Erevan (alt. 1000 m) and the torrid heat makes itself felt, as well as the pollution. With some difficulty we arrive at the travel agency to take possession of our minivan with a driver who will be completely at our disposition for the rest of the trip in the south of the country. Because the driver speaks neither French nor English, but a little German, Barbara will act as our interpreter, since she successfully handles Goethe's language mixed with Norwegian. The welcome at the agency is warm, they offer us some refreshment, everything happens smoothly with good will.

Everything is ready for this second week: the chauffeur and the minivan are available, we can leave in the direction of Lake Sevan via the autoroute! Don't be deceived by appearances -- it is nothing more or less than a national with little traffic. (Barbara's note: A national is a highway in France, smaller than an autoroute.) After a little more than an hour, we arrive. The hotel is vast, on the edge of the lake with a private beach, made to receive the numerous tourists of the ex-USSR countries, but since that time, it is a total flop. Whose fault? In spite of the hotel's luxury, we still have the problem of no hot water. We have to wait, but we don't have time because the dinner hour approaches. The restaurant is excellently situated on one of the lake's most visited sites, Bird Island, with its rustic monastery. We are the only clients, even though it is July. There is no menu, and we speak neither Armenian nor Russian, so we get a guided visit of the kitchen to choose our menu.

Tuesday, July 4: Sevan-Sevan: 86 km: 1 pass

We start off without luggage and follow the edge of the lake that is the most protected from the wind, where one can bathe on the narrow beaches that extend at the feet of the mountains. The sun comes up, it is mild, and the air is pure. What is more normal at 1900 m altitude? The fishermen are getting down to work on this site flooded with light whose power strikes all visitors. No where else in this country does the sky attain this purity and this intensity that it gets from the mirror of Sevan.

The road surface is good and one can see, along the length of the lake's edge, numerous rusty remains of worksites abandoned since the time of the fall of the Soviet system. At the 26th km we leave the lake for a small incursion to Karmir Pass (alt. 2176 m), near Azerbaijan, 8 km of climbing, rather a gentle climb, since we are not climbing trees (altitude change: 180 m). Returning to the lake, waiting in vain for our chauffeur with whom we have a rendez-vous, I take a small dip in the lake while Barbara photographs me. Then, returning to the hotel and seeing, several yards from the arrival, our chauffeur, who had to wake himself up from his nap!

The road surface is good and one can see, along the length of the lake's edge, numerous rusty remains of worksites abandoned since the time of the fall of the Soviet system. At the 26th km we leave the lake for a small incursion to Karmir Pass (alt. 2176 m), near Azerbaijan, 8 km of climbing, rather a gentle climb, since we are not climbing trees (altitude change: 180 m). Returning to the lake, waiting in vain for our chauffeur with whom we have a rendez-vous, I take a small dip in the lake while Barbara photographs me. Then, returning to the hotel and seeing, several yards from the arrival, our chauffeur, who had to wake himself up from his nap!

Wednesday 5 July: Sevan-Djermuk: 8 km: 1 pass

Today, a marathon stage...on four wheels. Almost 300 km, mostly on eroded terrain. The condition of the road surface is, at times, disconcerting. We follow the eastern side of the lake, the less visited, but not the less scenic. The road, well paved at the beginning, gives way to a track, riddled with holes like Gruyère. The minivan takes a special, slalom-like course, while the bicycles take up the shock in the back of the van.

You may wonder about the presence of an electrically powered train, if you will, in this desolate region on the borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan. If a train ventures up to here after having run alongside the steepest bank of Lake Sevan, it is because the surrounding area contains sizeable gold mines. Constructed (obviously by the Soviets) to carry gold from the mine at Zod to other regions of the ex-USSR where it was processed. Of its yellow metal, sent to Russia in lead train cars, Armenia saw almost none of the color (for you to judge). The topography explains the sparse population in these pasture areas, mostly given to animal raising. After this gymkhana, we branch off at Vardenis, standing against the volcanic chain crowned with snow, heading for Azerbaijan, to stop our vehicle at the terminus of the rail line at the Zod mine. Zod Pass (alt. 2366 m) invites us to climb it. Initially, the percentage is great on this unpaved road and, as Barbara has already chosen to climb on foot, I opt for the same. Four km of climbing, not the sea to drink, but an advanced military post looms up ahead of us. Interrogations? Parev (hello). We explain the goal of our presence here. I don't know if they understand our gibberish but when I talk to them about France and football (Djorkaeff, etc.) the barrier is raised! (Note to Americans: Football = soccer. Djorkaeff is a player of Armenian origin who is on the French national soccer team that had won the European championship a couple of days earlier.) At the summit, formerly considered the border with Azerbaijan, not a living soul. The border station was moved farther (down the Azerbaijani side) because of various armed conflicts. Returning to the vehicle, the day is far from over. We again pass alongside Lake Sevan until Martuni, a large agricultural village (market town) that, for the time being, is more interested in raising animals than in welcoming tourists. Door to the south of the country, the southern part of Armenia has long been excluded from tourist itineraries. This rural region with its "eagle-nest" villages often troglodytic (cave dwelling), was also, for a long time, considered as the most backward. First, however, we have to cross the powerful Vardenis chain (highest point: 3521 m), via Selim Pass (2410 m). The paved road...on the map has disappeared, giving way, from now on and surely until the end of time, to a trail in very bad condition where a 4x4 would be preferable to our minivan.

You may wonder about the presence of an electrically powered train, if you will, in this desolate region on the borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan. If a train ventures up to here after having run alongside the steepest bank of Lake Sevan, it is because the surrounding area contains sizeable gold mines. Constructed (obviously by the Soviets) to carry gold from the mine at Zod to other regions of the ex-USSR where it was processed. Of its yellow metal, sent to Russia in lead train cars, Armenia saw almost none of the color (for you to judge). The topography explains the sparse population in these pasture areas, mostly given to animal raising. After this gymkhana, we branch off at Vardenis, standing against the volcanic chain crowned with snow, heading for Azerbaijan, to stop our vehicle at the terminus of the rail line at the Zod mine. Zod Pass (alt. 2366 m) invites us to climb it. Initially, the percentage is great on this unpaved road and, as Barbara has already chosen to climb on foot, I opt for the same. Four km of climbing, not the sea to drink, but an advanced military post looms up ahead of us. Interrogations? Parev (hello). We explain the goal of our presence here. I don't know if they understand our gibberish but when I talk to them about France and football (Djorkaeff, etc.) the barrier is raised! (Note to Americans: Football = soccer. Djorkaeff is a player of Armenian origin who is on the French national soccer team that had won the European championship a couple of days earlier.) At the summit, formerly considered the border with Azerbaijan, not a living soul. The border station was moved farther (down the Azerbaijani side) because of various armed conflicts. Returning to the vehicle, the day is far from over. We again pass alongside Lake Sevan until Martuni, a large agricultural village (market town) that, for the time being, is more interested in raising animals than in welcoming tourists. Door to the south of the country, the southern part of Armenia has long been excluded from tourist itineraries. This rural region with its "eagle-nest" villages often troglodytic (cave dwelling), was also, for a long time, considered as the most backward. First, however, we have to cross the powerful Vardenis chain (highest point: 3521 m), via Selim Pass (2410 m). The paved road...on the map has disappeared, giving way, from now on and surely until the end of time, to a trail in very bad condition where a 4x4 would be preferable to our minivan.

The countryside is scenic and on this vast plateau at high altitude surrounded by summits, several farms are scattered. Given the delay due to the state of the road, I abandon the idea of riding the last five km of Selim Pass, especially because of the drizzle that has started to fall. After the summit, the descent is equally as trying, especially for our driver, who begins to feel exhausted. Impressive hairpin turns above an enormous drop -- it gives me goosebumps. Farther down in the valley, the pavement reappears toward the principal route that links Erevan to the High Karabagh, which was the object of bitter combats and of negotiations, where nature is more intimately felt and more smiling. The villages of the region, surrounded by small vineyards brightening the flanks of the mountains, give off, more than anywhere else in Armenia, the sweetness of life itself to the wine-making regions. It is very hot on this road that also links Iran, which is why we also run across tanker trucks with buckled wheels, making the shuttle to the capital. Then, heading west for a truly healthful promenade, because the end of the road is none other than the thermal station of national repute, Djermuk (alt. 2100 m) (the Armenian Vichy). The countryside becomes more imposing, nature seems to find its rights again in these out-of-the-way regions where dwellings are always more rare. The numerous natural springs that flow from the surrounding mountains have made the reputation of the cure station, of which the different buildings, rather sinister, were built during Soviet times in the Armenian national style, of pink tuf rock. The day has been long and trying. We are exhausted and, before getting to our room with apprehension, in one of these immense cure establishments, we are received with great pomp in the office of the director of the place.

The countryside is scenic and on this vast plateau at high altitude surrounded by summits, several farms are scattered. Given the delay due to the state of the road, I abandon the idea of riding the last five km of Selim Pass, especially because of the drizzle that has started to fall. After the summit, the descent is equally as trying, especially for our driver, who begins to feel exhausted. Impressive hairpin turns above an enormous drop -- it gives me goosebumps. Farther down in the valley, the pavement reappears toward the principal route that links Erevan to the High Karabagh, which was the object of bitter combats and of negotiations, where nature is more intimately felt and more smiling. The villages of the region, surrounded by small vineyards brightening the flanks of the mountains, give off, more than anywhere else in Armenia, the sweetness of life itself to the wine-making regions. It is very hot on this road that also links Iran, which is why we also run across tanker trucks with buckled wheels, making the shuttle to the capital. Then, heading west for a truly healthful promenade, because the end of the road is none other than the thermal station of national repute, Djermuk (alt. 2100 m) (the Armenian Vichy). The countryside becomes more imposing, nature seems to find its rights again in these out-of-the-way regions where dwellings are always more rare. The numerous natural springs that flow from the surrounding mountains have made the reputation of the cure station, of which the different buildings, rather sinister, were built during Soviet times in the Armenian national style, of pink tuf rock. The day has been long and trying. We are exhausted and, before getting to our room with apprehension, in one of these immense cure establishments, we are received with great pomp in the office of the director of the place.

Thursday, July 6: Djermuk-Djermuk: 69 km, 2 passes

A stage without baggage is appreciated, as is the azure blue of the sky. The air is cool at 2000 meters but in the valley (1300 m), the edge of which we rejoin in our vehicle, the heat also begins its day. We leave the minivan and our chauffeur, who can thus continue his night, at the foot of the first climb. On this side, the mountain and the climate are Mediterranean-no pasture land. We make the climb via a small road, calm, half paved, over approximately 15 km. It leads to the autonomous republic of Nakhitchevan that belongs to Azerbaijan. At the summit we come out at Agchac Pass (alt 1999m--too bad!). The countryside looks like a Van Gogh painting, and the peasants are working in the fields cutting hay with the means at hand--the scythe! Returning to the valley (1300 m) and without waiting any more in this furnace, we start the second and last climb of the day, more impressive because it is long--20 km. The air becomes more and more agreeable, the wind picks up, the sky is very full, and a thunderclap that says something to me in its own way obliges me to finish this climb at a sprint.

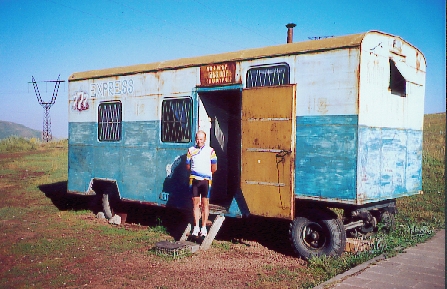

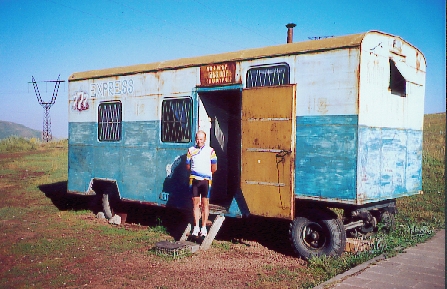

A little while later, Barbara reaches the summit of Voroton Pass (2344 m) just in time to take shelter in a trailer converted to a refreshment stand and sleeping car, when the first drops appear. She escapes a good drenching. First worries--how long will we be blocked in this refuge? But after one and one-half hours of forced rest, appreciable especially for Barbara, whose back is in knots, the sun reappears. After letting the road surface dry, I take the lead for the long descent, for Barbara descends as if on foot, which lets me get the car and go to meet her, since it is late. Returning to our hotel, we hasten to the dining room, to keep to the pension's schedule, for a meal that is not appetizing (not to turn up our noses, you understand!).

A little while later, Barbara reaches the summit of Voroton Pass (2344 m) just in time to take shelter in a trailer converted to a refreshment stand and sleeping car, when the first drops appear. She escapes a good drenching. First worries--how long will we be blocked in this refuge? But after one and one-half hours of forced rest, appreciable especially for Barbara, whose back is in knots, the sun reappears. After letting the road surface dry, I take the lead for the long descent, for Barbara descends as if on foot, which lets me get the car and go to meet her, since it is late. Returning to our hotel, we hasten to the dining room, to keep to the pension's schedule, for a meal that is not appetizing (not to turn up our noses, you understand!).

Friday, July 7: Djermuk-Goris (auto) 126 km

As always, early, we are comfortably seated in the minivan for a stage toward the extreme south of the country, called Zanguezour, named for the high mountain chain that constitutes the dorsal spine. The sun is already shining when we climb Vorotan Pass (2344 m) again, which we did on bicycles the previous day. No storm this time, the sky is completely clear. The summit attained, we can better see the curious Inca-style monuments on either side of the pass, as well as the fountain, very attractive to truck drivers (its water surely is miraculous). On the other side of the pass, the road descends gently, then crosses a vast plateau (which is not as flat as all that), dominated on the west by the jagged Zanguezour chain and riddled with volcanic rocks spit out millions of years ago by the high craters that spike the Karabagh plateau. At the outskirts of the village of Angechakot, a military barrier makes us give up the idea of climbing Bicanak Pass (2346 m) farther to the west, because, being next to the Azerbaidjani border, there might be some stray bullets. I keep my cool, externally, but I'm boiling inside. There is nothing for us to do but go directly to Goris, the town where this stage ends.

Nested in the forests that cover the surrounding mountains, the town was created during the Soviet time. Until then, the inhabitants of the region lived as if in the 5th century before our era, in troglodytic dwellings. Here, we stay in someone's apartment, an economic formula--that is to say, the occupants leave us their entire apartment and stay elsewhere! Aside from the usual problem of the lack of hot water, the apartment is well-kept and comfortable. However, Barbara puts the mattress on the floor because beds in this country are generally concave (hello, back!). But, before anything else, the afternoon offers itself to us for an excursion to the village of Khndzoresk. Banal, I say? Rather, fascinating, to see its curious cones of chalky stones bristling in the pastures and mountain slopes. These fairy chimneys that give this countryside false airs of Cappadoce are called, in France, "les demoiselles coiffées", a true masterpiece hidden from all tourism. For a bad beginning, the day's end is rather fortifying.

Nested in the forests that cover the surrounding mountains, the town was created during the Soviet time. Until then, the inhabitants of the region lived as if in the 5th century before our era, in troglodytic dwellings. Here, we stay in someone's apartment, an economic formula--that is to say, the occupants leave us their entire apartment and stay elsewhere! Aside from the usual problem of the lack of hot water, the apartment is well-kept and comfortable. However, Barbara puts the mattress on the floor because beds in this country are generally concave (hello, back!). But, before anything else, the afternoon offers itself to us for an excursion to the village of Khndzoresk. Banal, I say? Rather, fascinating, to see its curious cones of chalky stones bristling in the pastures and mountain slopes. These fairy chimneys that give this countryside false airs of Cappadoce are called, in France, "les demoiselles coiffées", a true masterpiece hidden from all tourism. For a bad beginning, the day's end is rather fortifying.

Saturday July 8: Goris-Goris: 31 km: 1 pass

The sky is covered and stormy, rather rare since the beginning of our stay. On the program auto + bicycle = 1 pass. A practical formula. We follow the road toward Iran, which it was necessary to restructure to allow the transit of Iranian heavy trucks that could not venture onto the bad mountain roads, barely suitable for motor vehicles. After playing leapfrog for about 50 kms, we arrive at the town of Gaban (alt. 750 m), the lowest altitude of the trip, a little village nested in a hemmed-in valley that attracts French engineers for the rich copper mines of the Zanguezour mountains. The town is dominated by powerful mountains whose snowy peaks attract climbers. The Zanguezour chain, with jagged summits (max alt. 3830 m), has a typically alpine appearance, which is different from the other Armenian mountains whose shapes are more round. The forest covering runs the length of the road, or almost, that goes to Iran, passing through the mining valley of Kadjaran (alt. 2000 m), where we get out of the van. As the crowning finale, Debaklu Pass (alt. 2535 m), the highest road pass in the country, a nice conclusion with, admittedly, a difficult beginning, but an appropriate end. The air there is cool. Barbara is far behind, but that is planned! because I am going to keep going to Aycinqil Pass (alt. 3707 m), 1200 meters higher. I am too greedy and foolhardy, for I set off into the unknown. On the map, a trail is mentioned, so why not? But after several kms on foot on a trail widened by excavation works. I become disillusioned. In front of me, an impasse, an enormous waterfall stares me in the face, and thinking more about it, I admit that the photo of the map dated approximately 40 years ago! leaves me little hope of finding the trail eaten up by vegetation. Too bad. As for the site, it is impressive, with summits and snowy ridges stuck in the mist. Returning to the vehicle at Kadharan, Barbara and the driver are relaxing...each on their own side, in a siesta while waiting for me. After this escapade in the south-Armenian mountains, long kept away from tourist itineraries but considered as one of the most authentic regions of the country, we rejoin our home at Goris, tired and satisfied to have, in a way, succeeded in this expedition to the unknown on the borders of the Caucasus.

Sunday, July 9: Goris-Erevan (auto) 300 km

Before taking the direction toward the capital, that is to say, crossing the whole country--almost 300 km, we can't leave this region without making a detour to one of the most handsome monasteries of Armenia: Tatev, located at the end of a road whose surface is of another age, with hairpin turns, winding in breathtakingly dizzy canyons with wooded slopes. Surrounded by powerful walls, the monastery collapsed in 1931 following a violent earthquake, and was restored in its entirety as it had been constructed in the 9th and 11th centuries. Few or no visitors this weekend. The Armenians have other fish to fry.

At present we can take the principal road to Erevan, beyond which the mountains and valleys are rather green or dry in places then,

as if by enchantment, opposite us, but in the distance, majestically circled by its snowy crown, rises the Agri-Dagi, better known by the name of Mount Ararat (alt. 5165 m) and flanked by its little brother, the Kukuk Agri-Dagi, "only" 3925 m high. A magic mountain in the same way as Fuji Yama (alt. 3778 m) is for the Japanese, Ararat constitutes an essential element of the Armenian geographic and symbolic countryside, but is located on the Turkish side. We are now on the illustrious and renowned Ararat plain, fertile and rich, abundant in useful things, vast agricultural spaces, orchards, fields, and vines that give this region its name of Armenia's wheat granary. Approaching Erevan, on both sides of the road, a succession of stands selling a little of everything 24 hours per day reminds us perhaps that one of the most important commercial roads of Asia passed by here, but a long time ago. It is still hot (more than 30º C) in Erevan and the air is rather doubtful in spite of the altitude (1000 m). We return to the hotel of the first day, still 500 rooms, leave our gear and to return the vehicle "and its driver" to the agency, then come back via the metro (ah, yes!) for a few cents, to the hotel. We've come full circle - oof!

as if by enchantment, opposite us, but in the distance, majestically circled by its snowy crown, rises the Agri-Dagi, better known by the name of Mount Ararat (alt. 5165 m) and flanked by its little brother, the Kukuk Agri-Dagi, "only" 3925 m high. A magic mountain in the same way as Fuji Yama (alt. 3778 m) is for the Japanese, Ararat constitutes an essential element of the Armenian geographic and symbolic countryside, but is located on the Turkish side. We are now on the illustrious and renowned Ararat plain, fertile and rich, abundant in useful things, vast agricultural spaces, orchards, fields, and vines that give this region its name of Armenia's wheat granary. Approaching Erevan, on both sides of the road, a succession of stands selling a little of everything 24 hours per day reminds us perhaps that one of the most important commercial roads of Asia passed by here, but a long time ago. It is still hot (more than 30º C) in Erevan and the air is rather doubtful in spite of the altitude (1000 m). We return to the hotel of the first day, still 500 rooms, leave our gear and to return the vehicle "and its driver" to the agency, then come back via the metro (ah, yes!) for a few cents, to the hotel. We've come full circle - oof!

Monday, July 10: the return

Departure in the shuttle from the hotel to the airport at 8:30 am, where the takeoff is at 10:30 am. No work interruption here, they will never be world champions of the strike like us (the French). No dilapidated Tupolev this time, but a good little Armenian Airlines Airbus (100 passengers), their only one in circulation, and after 4 hours 30 minutes of flight, we land in the cold of Roissy and summer (15º C)! What a contrast!

Charles Winter

Armenia, Part 1

Return to Bicycling à la Française

Barbara Leonard

The road surface is good and one can see, along the length of the lake's edge, numerous rusty remains of worksites abandoned since the time of the fall of the Soviet system. At the 26th km we leave the lake for a small incursion to Karmir Pass (alt. 2176 m), near Azerbaijan, 8 km of climbing, rather a gentle climb, since we are not climbing trees (altitude change: 180 m). Returning to the lake, waiting in vain for our chauffeur with whom we have a rendez-vous, I take a small dip in the lake while Barbara photographs me. Then, returning to the hotel and seeing, several yards from the arrival, our chauffeur, who had to wake himself up from his nap!

The road surface is good and one can see, along the length of the lake's edge, numerous rusty remains of worksites abandoned since the time of the fall of the Soviet system. At the 26th km we leave the lake for a small incursion to Karmir Pass (alt. 2176 m), near Azerbaijan, 8 km of climbing, rather a gentle climb, since we are not climbing trees (altitude change: 180 m). Returning to the lake, waiting in vain for our chauffeur with whom we have a rendez-vous, I take a small dip in the lake while Barbara photographs me. Then, returning to the hotel and seeing, several yards from the arrival, our chauffeur, who had to wake himself up from his nap!

You may wonder about the presence of an electrically powered train, if you will, in this desolate region on the borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan. If a train ventures up to here after having run alongside the steepest bank of Lake Sevan, it is because the surrounding area contains sizeable gold mines. Constructed (obviously by the Soviets) to carry gold from the mine at Zod to other regions of the ex-USSR where it was processed. Of its yellow metal, sent to Russia in lead train cars, Armenia saw almost none of the color (for you to judge). The topography explains the sparse population in these pasture areas, mostly given to animal raising. After this gymkhana, we branch off at Vardenis, standing against the volcanic chain crowned with snow, heading for Azerbaijan, to stop our vehicle at the terminus of the rail line at the Zod mine. Zod Pass (alt. 2366 m) invites us to climb it. Initially, the percentage is great on this unpaved road and, as Barbara has already chosen to climb on foot, I opt for the same. Four km of climbing, not the sea to drink, but an advanced military post looms up ahead of us. Interrogations? Parev (hello). We explain the goal of our presence here. I don't know if they understand our gibberish but when I talk to them about France and football (Djorkaeff, etc.) the barrier is raised! (Note to Americans: Football = soccer. Djorkaeff is a player of Armenian origin who is on the French national soccer team that had won the European championship a couple of days earlier.) At the summit, formerly considered the border with Azerbaijan, not a living soul. The border station was moved farther (down the Azerbaijani side) because of various armed conflicts. Returning to the vehicle, the day is far from over. We again pass alongside Lake Sevan until Martuni, a large agricultural village (market town) that, for the time being, is more interested in raising animals than in welcoming tourists. Door to the south of the country, the southern part of Armenia has long been excluded from tourist itineraries. This rural region with its "eagle-nest" villages often troglodytic (cave dwelling), was also, for a long time, considered as the most backward. First, however, we have to cross the powerful Vardenis chain (highest point: 3521 m), via Selim Pass (2410 m). The paved road...on the map has disappeared, giving way, from now on and surely until the end of time, to a trail in very bad condition where a 4x4 would be preferable to our minivan.

You may wonder about the presence of an electrically powered train, if you will, in this desolate region on the borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan. If a train ventures up to here after having run alongside the steepest bank of Lake Sevan, it is because the surrounding area contains sizeable gold mines. Constructed (obviously by the Soviets) to carry gold from the mine at Zod to other regions of the ex-USSR where it was processed. Of its yellow metal, sent to Russia in lead train cars, Armenia saw almost none of the color (for you to judge). The topography explains the sparse population in these pasture areas, mostly given to animal raising. After this gymkhana, we branch off at Vardenis, standing against the volcanic chain crowned with snow, heading for Azerbaijan, to stop our vehicle at the terminus of the rail line at the Zod mine. Zod Pass (alt. 2366 m) invites us to climb it. Initially, the percentage is great on this unpaved road and, as Barbara has already chosen to climb on foot, I opt for the same. Four km of climbing, not the sea to drink, but an advanced military post looms up ahead of us. Interrogations? Parev (hello). We explain the goal of our presence here. I don't know if they understand our gibberish but when I talk to them about France and football (Djorkaeff, etc.) the barrier is raised! (Note to Americans: Football = soccer. Djorkaeff is a player of Armenian origin who is on the French national soccer team that had won the European championship a couple of days earlier.) At the summit, formerly considered the border with Azerbaijan, not a living soul. The border station was moved farther (down the Azerbaijani side) because of various armed conflicts. Returning to the vehicle, the day is far from over. We again pass alongside Lake Sevan until Martuni, a large agricultural village (market town) that, for the time being, is more interested in raising animals than in welcoming tourists. Door to the south of the country, the southern part of Armenia has long been excluded from tourist itineraries. This rural region with its "eagle-nest" villages often troglodytic (cave dwelling), was also, for a long time, considered as the most backward. First, however, we have to cross the powerful Vardenis chain (highest point: 3521 m), via Selim Pass (2410 m). The paved road...on the map has disappeared, giving way, from now on and surely until the end of time, to a trail in very bad condition where a 4x4 would be preferable to our minivan.

The countryside is scenic and on this vast plateau at high altitude surrounded by summits, several farms are scattered. Given the delay due to the state of the road, I abandon the idea of riding the last five km of Selim Pass, especially because of the drizzle that has started to fall. After the summit, the descent is equally as trying, especially for our driver, who begins to feel exhausted. Impressive hairpin turns above an enormous drop -- it gives me goosebumps. Farther down in the valley, the pavement reappears toward the principal route that links Erevan to the High Karabagh, which was the object of bitter combats and of negotiations, where nature is more intimately felt and more smiling. The villages of the region, surrounded by small vineyards brightening the flanks of the mountains, give off, more than anywhere else in Armenia, the sweetness of life itself to the wine-making regions. It is very hot on this road that also links Iran, which is why we also run across tanker trucks with buckled wheels, making the shuttle to the capital. Then, heading west for a truly healthful promenade, because the end of the road is none other than the thermal station of national repute, Djermuk (alt. 2100 m) (the Armenian Vichy). The countryside becomes more imposing, nature seems to find its rights again in these out-of-the-way regions where dwellings are always more rare. The numerous natural springs that flow from the surrounding mountains have made the reputation of the cure station, of which the different buildings, rather sinister, were built during Soviet times in the Armenian national style, of pink tuf rock. The day has been long and trying. We are exhausted and, before getting to our room with apprehension, in one of these immense cure establishments, we are received with great pomp in the office of the director of the place.

The countryside is scenic and on this vast plateau at high altitude surrounded by summits, several farms are scattered. Given the delay due to the state of the road, I abandon the idea of riding the last five km of Selim Pass, especially because of the drizzle that has started to fall. After the summit, the descent is equally as trying, especially for our driver, who begins to feel exhausted. Impressive hairpin turns above an enormous drop -- it gives me goosebumps. Farther down in the valley, the pavement reappears toward the principal route that links Erevan to the High Karabagh, which was the object of bitter combats and of negotiations, where nature is more intimately felt and more smiling. The villages of the region, surrounded by small vineyards brightening the flanks of the mountains, give off, more than anywhere else in Armenia, the sweetness of life itself to the wine-making regions. It is very hot on this road that also links Iran, which is why we also run across tanker trucks with buckled wheels, making the shuttle to the capital. Then, heading west for a truly healthful promenade, because the end of the road is none other than the thermal station of national repute, Djermuk (alt. 2100 m) (the Armenian Vichy). The countryside becomes more imposing, nature seems to find its rights again in these out-of-the-way regions where dwellings are always more rare. The numerous natural springs that flow from the surrounding mountains have made the reputation of the cure station, of which the different buildings, rather sinister, were built during Soviet times in the Armenian national style, of pink tuf rock. The day has been long and trying. We are exhausted and, before getting to our room with apprehension, in one of these immense cure establishments, we are received with great pomp in the office of the director of the place.  A little while later, Barbara reaches the summit of Voroton Pass (2344 m) just in time to take shelter in a trailer converted to a refreshment stand and sleeping car, when the first drops appear. She escapes a good drenching. First worries--how long will we be blocked in this refuge? But after one and one-half hours of forced rest, appreciable especially for Barbara, whose back is in knots, the sun reappears. After letting the road surface dry, I take the lead for the long descent, for Barbara descends as if on foot, which lets me get the car and go to meet her, since it is late. Returning to our hotel, we hasten to the dining room, to keep to the pension's schedule, for a meal that is not appetizing (not to turn up our noses, you understand!).

A little while later, Barbara reaches the summit of Voroton Pass (2344 m) just in time to take shelter in a trailer converted to a refreshment stand and sleeping car, when the first drops appear. She escapes a good drenching. First worries--how long will we be blocked in this refuge? But after one and one-half hours of forced rest, appreciable especially for Barbara, whose back is in knots, the sun reappears. After letting the road surface dry, I take the lead for the long descent, for Barbara descends as if on foot, which lets me get the car and go to meet her, since it is late. Returning to our hotel, we hasten to the dining room, to keep to the pension's schedule, for a meal that is not appetizing (not to turn up our noses, you understand!).

Nested in the forests that cover the surrounding mountains, the town was created during the Soviet time. Until then, the inhabitants of the region lived as if in the 5th century before our era, in troglodytic dwellings. Here, we stay in someone's apartment, an economic formula--that is to say, the occupants leave us their entire apartment and stay elsewhere! Aside from the usual problem of the lack of hot water, the apartment is well-kept and comfortable. However, Barbara puts the mattress on the floor because beds in this country are generally concave (hello, back!). But, before anything else, the afternoon offers itself to us for an excursion to the village of Khndzoresk. Banal, I say? Rather, fascinating, to see its curious cones of chalky stones bristling in the pastures and mountain slopes. These fairy chimneys that give this countryside false airs of Cappadoce are called, in France, "les demoiselles coiffées", a true masterpiece hidden from all tourism. For a bad beginning, the day's end is rather fortifying.

Nested in the forests that cover the surrounding mountains, the town was created during the Soviet time. Until then, the inhabitants of the region lived as if in the 5th century before our era, in troglodytic dwellings. Here, we stay in someone's apartment, an economic formula--that is to say, the occupants leave us their entire apartment and stay elsewhere! Aside from the usual problem of the lack of hot water, the apartment is well-kept and comfortable. However, Barbara puts the mattress on the floor because beds in this country are generally concave (hello, back!). But, before anything else, the afternoon offers itself to us for an excursion to the village of Khndzoresk. Banal, I say? Rather, fascinating, to see its curious cones of chalky stones bristling in the pastures and mountain slopes. These fairy chimneys that give this countryside false airs of Cappadoce are called, in France, "les demoiselles coiffées", a true masterpiece hidden from all tourism. For a bad beginning, the day's end is rather fortifying.

as if by enchantment, opposite us, but in the distance, majestically circled by its snowy crown, rises the Agri-Dagi, better known by the name of Mount Ararat (alt. 5165 m) and flanked by its little brother, the Kukuk Agri-Dagi, "only" 3925 m high. A magic mountain in the same way as Fuji Yama (alt. 3778 m) is for the Japanese, Ararat constitutes an essential element of the Armenian geographic and symbolic countryside, but is located on the Turkish side. We are now on the illustrious and renowned Ararat plain, fertile and rich, abundant in useful things, vast agricultural spaces, orchards, fields, and vines that give this region its name of Armenia's wheat granary. Approaching Erevan, on both sides of the road, a succession of stands selling a little of everything 24 hours per day reminds us perhaps that one of the most important commercial roads of Asia passed by here, but a long time ago. It is still hot (more than 30º C) in Erevan and the air is rather doubtful in spite of the altitude (1000 m). We return to the hotel of the first day, still 500 rooms, leave our gear and to return the vehicle "and its driver" to the agency, then come back via the metro (ah, yes!) for a few cents, to the hotel. We've come full circle - oof!

as if by enchantment, opposite us, but in the distance, majestically circled by its snowy crown, rises the Agri-Dagi, better known by the name of Mount Ararat (alt. 5165 m) and flanked by its little brother, the Kukuk Agri-Dagi, "only" 3925 m high. A magic mountain in the same way as Fuji Yama (alt. 3778 m) is for the Japanese, Ararat constitutes an essential element of the Armenian geographic and symbolic countryside, but is located on the Turkish side. We are now on the illustrious and renowned Ararat plain, fertile and rich, abundant in useful things, vast agricultural spaces, orchards, fields, and vines that give this region its name of Armenia's wheat granary. Approaching Erevan, on both sides of the road, a succession of stands selling a little of everything 24 hours per day reminds us perhaps that one of the most important commercial roads of Asia passed by here, but a long time ago. It is still hot (more than 30º C) in Erevan and the air is rather doubtful in spite of the altitude (1000 m). We return to the hotel of the first day, still 500 rooms, leave our gear and to return the vehicle "and its driver" to the agency, then come back via the metro (ah, yes!) for a few cents, to the hotel. We've come full circle - oof!