Our Exploration of Various Tunnels

As I mentioned, a major portion of our vacation this time was spent either underground or below the sea level. It included exploring four different tunnels, each one fascinating in its own way.

Megiddo

We started with a tunnel in the ancient city of Megiddo, situated on top of a medium-sized hill. The purpose of the tunnel was to get water from a spring, located outside the city gates, into the city when it was besieged by an enemy. The tunnel starts with a vertical shaft accessible from inside the city. This shaft brings you to the horizontal portion of the tunnel, which leads to the remnants of the spring (now rather sad-looking) and to an exit on the hillside, outside the city limits.

Descending the obviously modern stairs into the tunnel, I kept wondering how they accomplished this in the ancient times. I didn't see any stone steps or such in the sides of the shaft. The best answer to that (from a tour guide in Jerusalem) is that they didn't necessarily go down into the shaft. The water from the spring filled the horizontal portion of the tunnel, and they just threw a bucket on a rope down the shaft to draw some water. The city of Megiddo, in addition to the tunnel, contains a wealth of archeological finds, including ruins of five ancient Canaanite temples and remnants of King Solomon's stables.

City of David

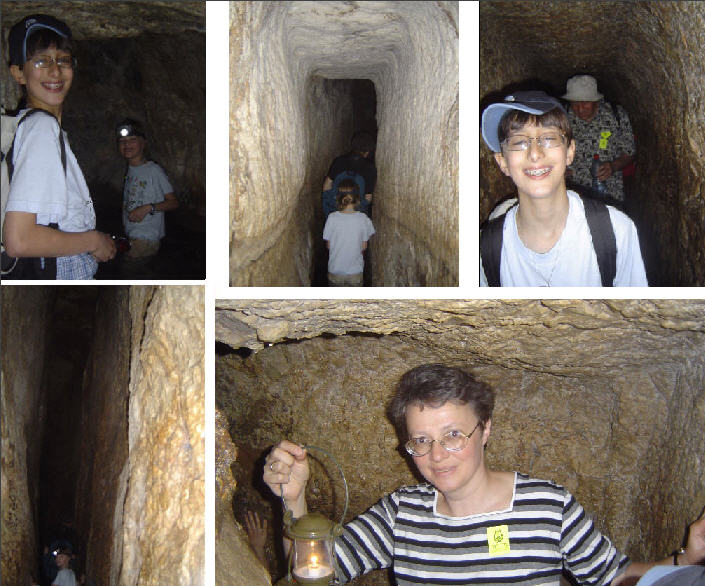

Then in Jerusalem, in the City of David located just outside the Old City walls, there are two tunnels serving essentially the same purpose. The first one predates Kind David and was used by his warriors to conquer the city from Jebusites about 3000 years ago. They found the hidden entrance to the spring, followed the tunnel, and then climbed up the water shaft to get into the city. It is all described in 2 Samuel 5:8. Here is the view of the upper end of the famous tsinnor, or water channel, which is now called Warren's shaft (named for an English archeologist).

King David's tunnel is now dry, because the waters from the Gihon spring are diverted into a newer and bigger tunnel built by King Hezekiah some 300 years later. The Assyrians were coming, and he had to secure the water supply. To save time, they were working from both ends towards each other, cutting through stone and obviously receiving directions to turn a bit to the left or to the right at several points, and somehow met in the middle. Modern scientists still haven't figured out how they managed that. At first I said irreverently that they were probably singing really loud, but after going through it and seeing for myself I was really impressed. The tunnel is about 500 m long and the water ranges between knee-deep and waist-high. If you decide to go, wear quick-drying clothes and Teva-type sandals, and carry a flashlight. You can change your shoes (but not clothes, unfortunately) at a bench near the exit.

Old City

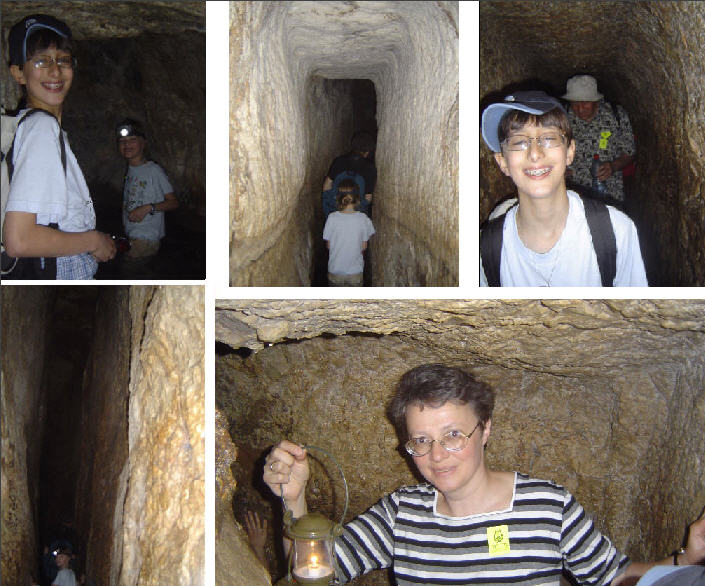

And finally, the famous Hasmonean tunnel, which starts near the Western Wall (that is, the specific area where Jews come to pray nowadays) and follows -- underground -- along the whole western retaining wall of the Temple compound to where it meets with the northern wall, with an exit to Via Dolorosa. The retaining walls enclosing the Temple compound were build by Herod, who was partial to big and elaborately decorated constructions. Therefore all the stones used in these walls were huge and had a decorative border, as you can see in the lower-left photo below. In the upper-right corner, Temma and I are touching the wall at a place which, if you rely on Euclidian geometry rather than emotion, is even holier than the Western Wall because it is closer, along the wall, to the location of the former Temple and the Holy of Holies (cathetus vs. hypotenuse). The women next to us came there specifically to pray (men, of course, pray in a different section where no women -- and therefore no coed tours -- are allowed). The remaining two photos show a portion of rock-cut Hasmonean aqueduct (upper-left) and public reservoir (lower-right) near the northern exit from the tunnel.

<< Back to main report