Marc Edwards: Jazz Takes on Many Forms

by Noah Kravitz

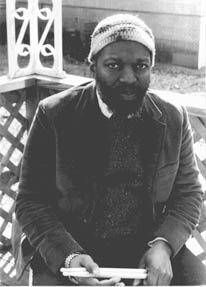

Marc Edwards (pictured in photo by Mette Tronvall)

didn't want to start Alpha Phonics, his record label, but

he had no choice. As the drummer explains it, "I wanted to get creative

music out to the public," and there were no ready takers for his music

among the established record companies, so he founded the company in  1991. His first release, Black Queen, was actually recorded in 1990, and Edwards

kept the tapes until he could publish the disc himself the next year. In

1993 Time and Space,

Vol. 1, featuring the drummer in a quartet

with Rob Brown, Hilliard Green, and Cara Silvernail, was the second Alpha

Phonics release.

1991. His first release, Black Queen, was actually recorded in 1990, and Edwards

kept the tapes until he could publish the disc himself the next year. In

1993 Time and Space,

Vol. 1, featuring the drummer in a quartet

with Rob Brown, Hilliard Green, and Cara Silvernail, was the second Alpha

Phonics release.

Influenced equally by a strong spiritual sense of self

and his keen awareness of American culture, Edwards's music is marked by

his fierce, creative drumming and the readily discernible logical structures

in his compositions.

"Free Jazz isn't really so free like people tend to

think it is," he explains. "You have to pay attention to the music-to

what the other musicians are doing. It's not just some free-for-all. The

way my pieces are, the musicians have the freedom to work within certain

areas of the composition."

Edwards, who makes his home in Queens, New York, likens

segments of his pieces to areas of a city, defined territories to be explored

during a specific time. "We'll have a section where, say, the area

from Fortieth to Forty-second Streets between Fifth and Seventh Avenues

is mapped out. And you can be free and creative within that specific area

as long as we're in that section." When you listen to Time and Space,

that concept is apparent: one quickly realizes the musicians are in the

same defined territory, exploring ideas on a similar theme and playing off

one another tonally and rhythmically, as well as on a conceptual level.

Outside of his Alpha Phonics projects, Edwards is best

known for his work with Cecil Taylor on the 1976 concert recording Dark

to Themselves. The drummer now keeps a quiet musical schedule during

the winter months but is looking forward to performances and a possible

album release this spring. "I like to hibernate now during the winter,"

he says. "Jazz cats always are out playing every chance they get, through

the cold and snow, but I feel you need time to take care of yourself. Classical

musicians don't tour during the winter, and there's a reason for that. It's

a pain lugging these drums around through the snow and ice!"

A trio album, Red Sprites and Blue Jets, with Sabir

Mateen on tenor sax and Hilliard Greene on bass, is forthcoming on the CIMP

label, and Edwards plans to play with the group, sometimes augmented by

Peter Mazzetti on guitar, in New York in a few months.

"My management would like to get me over to Europe,

so we'll see," he says. "That tour with Cecil in 1976 was the

first time I'd been on the road, and it was so nice to see such a completely

different reaction to the music over there. The level of audience response

and enthusiasm was tremendous. The young kids were asking such knowledgeable

questions; they knew so much about the history of the music. I'd like to

go back sometime."

Edwards believes that increased television exposure for

Jazz artists would do much to generate that kind of following here in America.

"We've got to get Jazz on TV," he says. BET on Jazz is

on now, but you can't get that everywhere."

Citing the negative influence of some of today's popular

music like gangsta rap on teens, Edwards argues for more a responsible attitude

from "so-called artists" and a broadening of mainstream culture.

"Young artists today can get a name a little too quickly, and that

kind of hype can be bad for them," he explains. "Once they get

a name, they start acting silly. There's a negative influence coming down

from some of the gangsta rappers right now; they should be exhibiting a

positive influence on the youth instead."

The drummer's words about positivity don't ring hollow;

the liner notes to his albums are filled words of thanks and praise to friends

and mentors, and Edwards's own poems and compositional notes center on the

exploration of "the spiritual self."

Though Alpha Phonic's recordings may not yet have achieved

the commercial popularity of, say, Tha Dogg Pound, Edwards maintains

that "if the kids had the chance to hear us, they'd come hear us."

He points to a show in October of 1995 at the Academy in New York as evidence

of the music's potential to draw young audiences. "We opened for Thurston

Moore of the rock group Sonic Youth, so there were a lot of young people

in the audience who'd never heard of us. They were receptives, they were

enthusiastic about the music," he recalls.

The problem for Edwards lies in the commerciality of the

culture and the limited breadth of music kids are exposed to through radio

and television. "Our culture is so ingrained with the backbeat that

you can put anything on it and do well," he explains. "The music

I'm playing isn't really so hard. If you find it hard to listen to, start

with Coltrane." By listening to Coltrane's works chronologically, he

explains, the movement away from bebop to free Jazz is easier for the listener

to adjust to. "You just start at the beginning and listen through to

his progressions with rhythms and harmonics. It all makes sense that way."

Even though he harbors some dissatisfaction with mainstream

American culture, Edwards would be the last person to discount the importance

of youth on the growth of Jazz today. "Cats think influence is like

water coming down from a mountain or rain falling." Edwards's voice

becomes animated as he draws the analogy. "They think it only travels

in one direction. That's not true; it's a two-way street.....You hear sounds

from younger players and pick up on them."

Without a doubt, when you pick up one of Edwards's Alpha

Phonics recordings, you're in for some powerful music. But to see him live

when he hits the streets of New York again this spring, that will be an

experience!

by Noah Kravitz

1991. His first release, Black Queen, was actually recorded in 1990, and Edwards

kept the tapes until he could publish the disc himself the next year. In

1993 Time and Space,

Vol. 1, featuring the drummer in a quartet

with Rob Brown, Hilliard Green, and Cara Silvernail, was the second Alpha

Phonics release.

1991. His first release, Black Queen, was actually recorded in 1990, and Edwards

kept the tapes until he could publish the disc himself the next year. In

1993 Time and Space,

Vol. 1, featuring the drummer in a quartet

with Rob Brown, Hilliard Green, and Cara Silvernail, was the second Alpha

Phonics release.