Extreme Lawn Ornaments |

By Gwendolyn Holbrow

Art: most people think it looks pretty and hangs on the wall. Since you are reading this magazine, you probably recognize a wider spectrum of objects and experiences as art, but you still expect to encounter it in museums and galleries, studios and sculpture parks. After all, that’s how you know it’s art, right? So what happens when art ventures outside its ghetto, or even moves in right next door? Local sculptors contend with a wide range of reactions to their XLOs (extreme lawn ornaments).

In Eric Wild’s Newton backyard, the remnants of his own lost civilization rise from the swamp. A path of ten blue disks about three feet across rises slightly above the duckweed and dark water, leading to the focal point, a twenty-foot-tall tower of steel and Plexiglas. At its core stands the central reactor, lit from within and studded with symbolic objects, like the lukasas (memory boards) Wild encountered during a stay in West Africa. Seated around the tower on a raised platform, five nearly life-sized figures made of two-by-fours gaze meditatively toward the center. A bright yellow pentagonal catwalk, a few feet above the water, surrounds the tower, enclosing five trapezoidal trays of green turf in the open spaces between its spokes.

To reach the platform, the visitor must step from one blue circle to the next, passing an eight-foot reset switch, a grid of orange squares hanging from wires stretched between the willow trees, and a decaying humanoid of chicken wire and wax ascending a narrow climbing wall. Basking frogs, disturbed, leap and splash below. The well-balanced visitor can continue along the narrow yellow walkway, over a bridge that includes blue wood rectangles and transparent Plexiglas boxes, and into a narrow thatched hut. Inside, a seven-sided chamber of mirrors displays the viewer in an infinite honeycomb of self-clones.

Wild, a sculptor and carpenter, considers the swamp a body of work. “It’s everything I’ve been thinking about for about three years,” he says. The tower section dates back to art school, other parts to his days in the 9 Yards art collaborative, and some are as recent this month. “Now it’s like a relic, a ruin. That’s how I see the whole swamp now, like making this little lost world…making my own sort of mystical culture.” He calls the reset switch the joke piece of the swamp, saying, “It’s like the African shaman of our society: ‘Reset your values.’” Wild says the piece is completed by the presence of people, and he uses it as a site for parties and performances.

Local reception has been mixed. “It’s great being in Newton,” says Wild. “In Brighton everyone was afraid to talk to us. There were rumors that we were a cult.” Now people walking their dogs often stop to chat. “They’re sort of a safe distance away, not in my world. It gives them a chance to say a lot of things,” he explains.

Even so, there have been problems. Wild installed lights in the swamp, originally leaving them on all night, and it became a popular partying place for teenagers. Neighbors called the police, who told Wild the lights had to be turned off by 10:30 every night, so now they’re on a timer. The installation was also a target of last year’s high school scavenger hunt. A figure from the platform (at that time, they were made of heavy plaster) was awarded the highest number of points in the hunt. “At 2 a.m., people were begging for one, offering to give us beer and drugs,” says Wild. “One girl pulled one off and waded through the swamp with it, and was dragging it up the hill. It’s cooled off some since then.”

Of the two families next door, “One of them, the guy is great, and the other one, they have teenagers and the parents are scared of me, I think,” Wild says, adding, “The best are the little kids. This kid was just staring at it and saying what’s this and what’s that. It was great.” A house painter perched on a ladder nearby, when asked his opinion, pronounces the installation “kinda weird.” And what does the landlord think? “He’s never seen it,” says Wild.

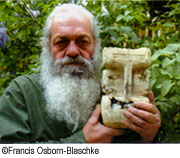

Sculptor Konstantin Simun of Allston has had more serious run-ins with the law. Originally from Russia, he is widely respected in both his native land and the United States. Locally, he is best known for Doo-doo, the golden puppet who sits on a granite post in Harvard Square commemorating street performer Igor Fokin, and for Totem America, a fixture at the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park for the past decade.

In 1988, just one week after arriving in America, Simun looked into a trash container and saw people looking back at him. The faces gazing out were discarded plastic jugs: reversed, the handle becomes a nose, with eye sockets on either side. He began collecting the plastic waste of his new land and converting it into the haunting faces that have become his signature here. For Totem America, he built a columnar wire cage over twenty feet tall, filled with these faces and other colorful plastic refuse, and crowned with orange traffic cones; a trenchant commentary on our culture of consumption. In 1992, he loaned the piece to the DeCordova, where it served as cover photo on the sculpture park brochure. Last November, due to weathering, the DeCordova finally asked him to uninstall it. Simun brought it back to his yard in Allston, where it rests in pieces among other finished sculpture, works in progress and raw materials.

To the trained eye, Simun’s yard is a lush sculpture garden, bursting with hundreds of pieces of his art. A path wanders past flowerbeds, garden furniture and a statue of Aphrodite. Monumental Egyptian heads stand guard and ancient mask-like faces gaze down from the surrounding walls. A grape arbor arches over his granddaughter’s sandbox. A golden Cadillac stands in the driveway.

Unfortunately,

some of Simun’s neighbors have untrained eyes, and when they look into

his garden they see only piles of trash. Aphrodite, a plaster torso with

pink seashell vulva, stands in an abandoned shower stall, and the garden

furniture includes an ironing board. The Egyptian heads used to be plastic

golf-club carriers from Building 19. The faces on the walls are made from

milk and detergent bottles, some bursting out of an old mattress, others

wearing fluorescent orange pointed hats that once were traffic cones.

The grape arbor trellis includes milk crates and electrical conduit. A

No Trespassing sign rests on the Cadillac’s hood, with a howling red face

made from a gasoline container bursting violently through the center.

Unfortunately,

some of Simun’s neighbors have untrained eyes, and when they look into

his garden they see only piles of trash. Aphrodite, a plaster torso with

pink seashell vulva, stands in an abandoned shower stall, and the garden

furniture includes an ironing board. The Egyptian heads used to be plastic

golf-club carriers from Building 19. The faces on the walls are made from

milk and detergent bottles, some bursting out of an old mattress, others

wearing fluorescent orange pointed hats that once were traffic cones.

The grape arbor trellis includes milk crates and electrical conduit. A

No Trespassing sign rests on the Cadillac’s hood, with a howling red face

made from a gasoline container bursting violently through the center.

“Some neighbors like it, ask when it would be possible to see it, but not every neighbor, believe me,” says Simun. One was incensed enough to lodge an anonymous complaint with the Boston Inspectional Services Department last December, and now the artist is embroiled in legal battle with the city, called to hearings and threatened with daily fines. To some extent, he can take this in stride. In 1998, the city tried to fine him $300 per day, but eventually charges were dismissed. This time the fines are only $50 per day. “Maybe next year, $25,” says Simun resignedly.

But the struggle takes its toll. He needs to keep his raw materials out where he can see them, because he will often contemplate an object for years before understanding its artistic destiny. “When the inspectors came, they said they have a policy,” explains Elena Simun, his wife, “If artists work in the yard, they can use 25%.” Now, when he looks at his collection of objects, instead of insight or inspiration, Simun says bitterly, “I need to think about 25%, ticket, inspection, police.” He gestures toward a recent creation, a rickety wooden chair with pointed nails poking up through the seat. “Now I feel my life is mostly like this chair.”

In Simun’s view, art is vital to society. “It’s important even for people who don’t go to museums. It’s very important for life,” he states. “Of course food is important too. But not just food.” Distressed over being fined for displaying art, he proposes, “My neighbors, they don’t have any art. They should pay because they don’t have any art.”

Joseph Wheelwright’s sculpture, particularly the stone heads and tree people, is familiar to DeCordova visitors and also to his neighbors on Ashmont Hill in Dorchester. To the left of his front path, a large head covered with white pebbles peers over the hedge. Goat Boy, a pale stone head, nestles in the earth alongside the path. Behind the hedge on the right, sinuous wooden legs reach for the sky; perhaps a tall tree person practicing handstands? A decaying wooden man sprawls on the grass nearby. In back, a slender cedar woman has leaned suggestively against a larger tree for so long they have begun to grow together. And high above all, a buck-toothed caped crusader of bricks and mortar stands astride the chimney cap.

Perhaps because his work employs more traditional materials, perhaps because there’s not quite so much of it, or because the colors are more muted, Wheelwright has experienced more positive feedback. “People like it. People stop and ring the bell. I don’t think I’ve had any negative comments at all, no vandalism at all,” he says. “No problems at all.” The only negative response comes once a year, when he brings out the eerier figures from the porch: “On Halloween, we drag some of these things out, send the kids away crying in fear.”So far, Wheelwright’s concerns about living in what he calls a “rough neighborhood” have also been unfounded. In fact, like Wild, he has discovered that teenagers appreciate his work, in their own way. One day a row of ten boys ran through the yard in a line, past the cedar woman. “They reached up and felt her breasts and ran around the house,” says Wheelwright. Other than that, “There’s never been a problem here, knock on wood…and stone.”

Wheelwright agrees with Simun on society’s need for artists. According to him, “They make life more vivid” for everyone else, and serve as “a safety mechanism” into the future. Although he hasn’t had any trouble at home, Wheelwright has struggled with authorities in the past over studio zoning requirements. “If they want artists in their town, exceptions should be made for them,” he says. Wheelwright believes that society benefits from diversity, and that local governments need to lighten up and lay off. “That’s why it’s nice in Vermont,” he adds, where he has a second studio. But for Massachusetts artists, “Not In My Back Yard” can come perilously close to “Not In Your Back Yard Either.”