What's here:

The era of minicomputers (for "minimal" -- not "miniature" -- computer) lasted from 1960, or so, heralded by DEC's PDP-1 until the early 1980s when they began to be replaced by microprocessors. Like all other things, minicomputers grew and evolved over time and occupied many niches in the computing world. Designed to be simple, good performers, and of reasonable price, these machines changed the world.

The birth of the minicomputer brought forth human exposure to computers

that simply wasn't possible during the era of "Big Iron" (or "Heavy

Metal", as it's sometimes called). Machines of the '50s, and indeed the

mainframes of the '60s, were large, complex, and sometimes cantankerous

creatures which occupied large heavily air- conditioned rooms and

frequently had at least one full- time engineer on site to look after

their care and feeding. (For a good view of "Big Iron", I recommend Mr. Paul

Pierce's excellent

Web site

![]() .) A typical

minicomputer needed none of these support systems.

.) A typical

minicomputer needed none of these support systems.

Eventually minicomputers evolved into the 32-bit so- called "supermini"

configurations as exemplified by DEC's VAX series and DG's MV architecture

before slowly dying out from competition by microprocessor- based

machines. (Mr. Tom Carlson maintains an excellent

Obsolete Computer Museum

![]() which is well worth a

look and features early microcomputers.) During their reign, however, minis

touched tens of thousands of lives and brought the world of computing to

the common man.

which is well worth a

look and features early microcomputers.) During their reign, however, minis

touched tens of thousands of lives and brought the world of computing to

the common man.

Minicomputers are now, for the most part, forgotten by the main stream; the few that remain (many as dedicated controllers) are a bit forlorn today. The average PC on your desk may pack several dozen times the raw computing power of the average "mini". Most of these machines are now regarded as little more than "trash" and, sadly, many end up in landfills!

Enter the "computer preservationist"!

Happily, some people began to notice the sad waste that the wholesale discarding of this technology was taking on our history and decided to act. These folks acquired systems, many of which were fully functional, and saved them before they could be shredded and melted for scrap metal. Happily, the world seems to be teeming now with individuals interested in preserving these bits of history, and the Internet is a wonderful place to "meet" those similarly inclined.

There are too many people I've met to list here in the text, but I've compiled

a list of

interesting links ![]() which

you can peruse. I'm honoured to be in their company.

which

you can peruse. I'm honoured to be in their company.

Many people are unaware that such a beast as a "minicomputer" ever existed. Typically, these are folks who grew up in the era of the PC and never looked back in time to see what preceeded them. These pages will attempt to shed some light on the matter.

A minicomputer, or minimal computer, is designed from the outset to be simple in nature, economical to build, and inexpensive for a purchaser to acquire and operate. Unlike typical mainframes which had a bewildering array of capabilities, minicomputers were engineered to perform well with a minimum of complexity. Typically, a minicomputer would forego the use of data channels and special- purpose I/O controllers in favour of a simple I/O bus structure, sometimes even without DMA capabilities. That said, I feel it should be mentioned that some minicomputers did have such features built into them, especially toward the end of the line.

Many "minis" sported word lengths of 16 bits, although some had 18, 12, or even 36 bits, the word length being defined as the width of the ALU or Arithmetic/Logic Unit. Virtually all of them had mainstore capacities measured in Kilobytes (not Megabytes). Typically the instruction sets were simple affairs, but not always, rarely exceeding more than 50 or 60 different instructions and the number of registers was usually modest with the largest minis having perhaps sixteen.

What were they used for? Minicomputers enjoyed a large success in

process control and instrumentation tasks. Some, like the

PDP-12

![]() were designed especially for use in laboratories and received wide use in

the medical field. Some minis were used in schools for teaching purposes; my

Nova 840

were designed especially for use in laboratories and received wide use in

the medical field. Some minis were used in schools for teaching purposes; my

Nova 840

![]() came from such an environment. A moderately well- to- do individual could

even purchase one for use at home if so desired.

came from such an environment. A moderately well- to- do individual could

even purchase one for use at home if so desired.

How big are they? As mentioned before, minicomputers aren't really miniature; they tend to be rack- mounted affairs weighing 75 or 80 pounds for the CPU alone. Large systems like the PDP-12 can weigh upwards of 700 pounds and stand six feet tall. Most of mine are 19 inches wide and about 24 inches deep; heights tend to be either 10 1/2 or 5 1/4 inches.

I started this all on a lark -- almost by accident. I've always been a pack- rat by nature, and have an abiding love of computing systems, so if the collection seems a bit eclectic, that's why. I never intended on becoming a computer collector -- it just happened.

As currently defined, my collection is primarily of CPUs

(Central Processing Units) in the 16 bit category. I chose this

line since those were the machines most endangered by "upgrading" at the

time I began acquiring antique hardware and were readily available (for the

"right price"). I'm a CPU "head" anyway; always have been. For the most

part, my machines consist of those of

Data General Corporation

![]() and

Digital Equipment Corporation

and

Digital Equipment Corporation

![]() manufacture, although there are a couple of other companies represented.

manufacture, although there are a couple of other companies represented.

My first big "score" was back in 1985 (I think...) when I acquired a DG

Nova 1210 ![]() .

Fairly short on the heels of that find, I found myself with a DEC

pdp11/20

.

Fairly short on the heels of that find, I found myself with a DEC

pdp11/20 ![]() .

Being literate in the field of hardware repair, a friend of mine

asked me to fix his 11/20 machine for him to use as a home computer. I got the

machine running, and it seems he lost interest in it. The 11/20 now sits

in my dining room (I still regard it as someone elses property, and if he

wants it back he's got it) sharing rack space with a DEC

pdp11/34a

.

Being literate in the field of hardware repair, a friend of mine

asked me to fix his 11/20 machine for him to use as a home computer. I got the

machine running, and it seems he lost interest in it. The 11/20 now sits

in my dining room (I still regard it as someone elses property, and if he

wants it back he's got it) sharing rack space with a DEC

pdp11/34a

![]() , an

11/23

, an

11/23

![]() (in an

11/03 box), and a dual

RX-02

(in an

11/03 box), and a dual

RX-02

![]() floppy drive.

floppy drive.

My primary focus is on processors and most of the machines are fully

functional. I am not overly averse to using modern memory, mass storage, and

interface devices (although I do place importance in keeping machines more

or less "original") where required to allow functionality of a processor; I

routinely use my DG/One

![]() to interface with a

Nova 840

to interface with a

Nova 840

![]() ,

and have designed (though not yet built) a memory replacement system for the

Nova 1210 (which has faulty memory) using modern static memory chips.

Hopefully there are disk, memory, and peripheral enthusiasts out there to

fill the gaps I've left!

,

and have designed (though not yet built) a memory replacement system for the

Nova 1210 (which has faulty memory) using modern static memory chips.

Hopefully there are disk, memory, and peripheral enthusiasts out there to

fill the gaps I've left!

I do posess some complete systems; the

Nova 840

![]() is complete and functional, as are the

pdp11/23

is complete and functional, as are the

pdp11/23

![]() ,

the

PDT-11/150

,

the

PDT-11/150

![]() ,

and the

InterAct 32C

,

and the

InterAct 32C

![]() (although the latter has a 32 bit microprocessor as it's brain). The

PDP-12/30

(although the latter has a 32 bit microprocessor as it's brain). The

PDP-12/30 ![]() and pb 250

and pb 250 ![]() are also fully configured.

are also fully configured.

The pdp11/34a was acquired as a complete system, but the expansion rack

and peripherals were lost when my family disposed of them without my

knowledge or consent. Currently, it shares the RX-02 drives with the

pdp11/23 system, and I power it on (dimming the neighbourhood lights in

the process) when I need to use the tape drive (which, blast it, is broken

at the moment).

The Nova 840 was an especially wonderful find; it had been powered off only a few months prior to my acquiring it, and the person in charge of it had been told to "make it disappear". Fortunately, I happened to be snuffling about, got wind of this, and helped the machine to "disappear" into a good and loving home instead of a dump. It's also the very same machine I first "cut teeth" on in secondary school. I have a fairly extensive set of spares for this machine as well as a full set of technical documents, including logic prints. As long as TTL logic is available, the magnetic cores don't break, and the disk heads don't crash, this machine will run.

The DG Eclipse S/230

![]() was acquired

as a full system (originally a Calma CADD system, with the graphics stuff

stripped out) minus the CDC 300 Mb SMD disk drives (The power to drive them

(208 VAC) is seldom available in residential areas, nevermind apartments).

was acquired

as a full system (originally a Calma CADD system, with the graphics stuff

stripped out) minus the CDC 300 Mb SMD disk drives (The power to drive them

(208 VAC) is seldom available in residential areas, nevermind apartments).

I've got all sorts of other stuff as well. This introduction only touched

on the highlights of my collection. For a complete listing, please see the

Collection Catalogue

![]() .

.

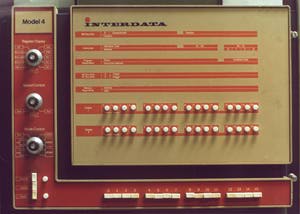

There's a fairly extensive set of technical manuals here as well. I posess

full logic prints for all the machines I have save the Eclipse S/140, the

IBM RS/6000s, and the DEC VAXen. I also have the prints and doco for other

machines which I don't have in the collection, such as, the pdp11/70, the

pdp11/44, the Interdata Model 3, and DEC's KI-10

![]() processor (YES!). I've

also got several manuals (by my acquisition and my wife's) on various

machine architectures and programming. Between us, we've got lots of so-called

"programming cards" and other oddball documentation. I'm in the process of

making a catalogue of all the paperwork (It's time-consuming work..).

processor (YES!). I've

also got several manuals (by my acquisition and my wife's) on various

machine architectures and programming. Between us, we've got lots of so-called

"programming cards" and other oddball documentation. I'm in the process of

making a catalogue of all the paperwork (It's time-consuming work..).

If you're interested in these machines for their operating systems and

basic architecture and can't get hold of one for yourself, don't despair!

Mr. Robert Supnik has written simulators

![]() for DG's Nova and DEC's

pdp11 (as well as a good many other DEC processors as well) that run on a

large variety of modern platforms.

for DG's Nova and DEC's

pdp11 (as well as a good many other DEC processors as well) that run on a

large variety of modern platforms.

![]()