Elbridge Trask was born on July 15, 1815 at Beverly, Massachusetts and died on 6-22-1863 Tillamook, OR. He is buried at the Fairview Pioneer Cemetery near the Trask River.

Elbridge is the son of John Trask, b: 5-7-1780 Beverly, Essex, MA [s. Osman + Molly(VR)] also a mariner and Bethia or Bethiah Twiss married on 12-5-1802 Beverly, Essex, MA (VR), b: 12-10-1781 Beverly, Essex, MA [s. Robert + Huldah(VR)] Elbridge is a descendent of Osmunde Traske. At this writting, there is at least one direct Trask descendents of Elbridge named Trask 1.

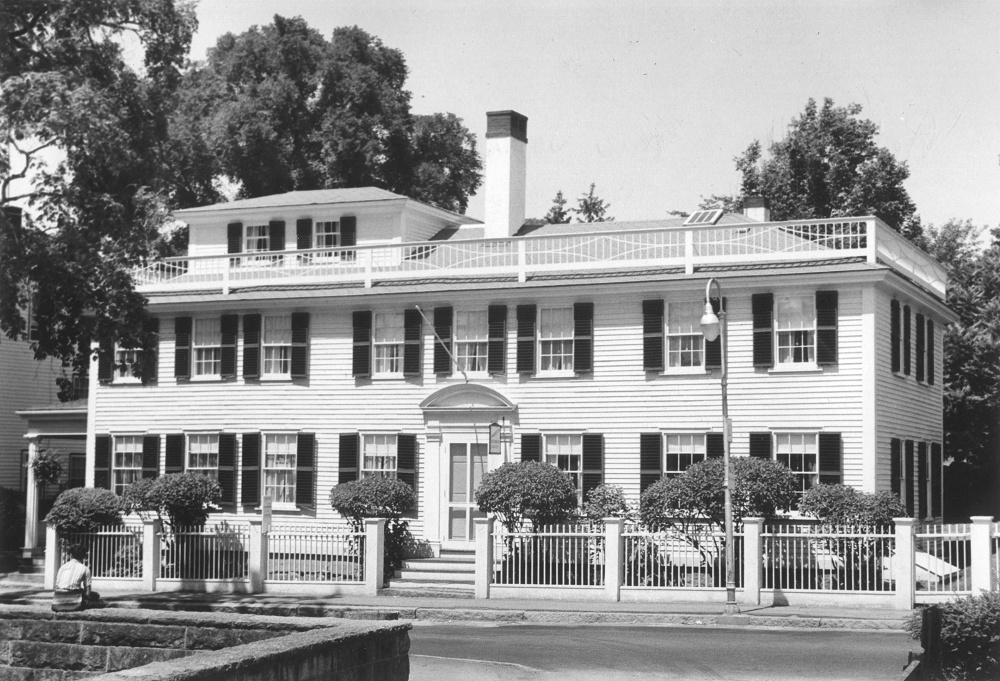

The Trask family was one of the earliest pioneer families of the Bay Plantation. They had lived for generations at Trent and East Coker, Somersetshire, England. Captain William Trask, a cousin of Osmund Trask had been at the fishing station at Cape Ann before John Endecott arrived with the first shipload of settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Company.2 Captain William Trask later became the military commander of the Bay Plantation.

During the nineteenth century an atmosphere of excitement and adventure existed in the Bay Plantation. Men and ships from the area spread all over the world seeking trade and adventure. It was in this atmosphere that a Boston ice merchant named Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth became interested in the business prospects of the Oregon country. He enrolled in Hall Jackson Kelley's American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of Oregon, founded in 1829.3 In 1831 Nathaniel Wyeth organized a joint-stock company to trade for furs on the Columbia River.

In 1832, Wyeth set out with a small company of men, to travel across the continent to the Oregon country. Before Wyeth had left Massachusetts he had made arrangements to make purchases of trade goods from the brig "Sultana" which was sailing later to the mouth of the Columbia River. Wyeth's harrowing adventures in crossing the continent have been well documented. He witnessed many exciting events including the 1832 fur trappers rendezvous at Pierre's Hole west of the Teton Mts. On reaching the Columbia River, Wyeth learned that the brig "Sultana" had wrecked in the South Pacific.

After a couple of years of business maneuvers and adventures in the west, Wyeth decided to take a supply trade goods to the Columbia country. On July of 1834 he began work on a fur trading post on the Snake River in what is today southern Idaho. He named the post Fort Hall. He had made arrangements in January of that year for the Captain of the ill-fated brig "Sultana" to bring another ship loaded with supplies to the Columbia River. Captain James Lambert arrived at the Columbia from Oahu with the brig "May Dacre" in mid-september. Since Weyth had planned to fill the "May Dacre" with dried salmon for the return to Boston and the salmon run had already taken place, he dispatched the "May Dacre" on another trading trip to the Hawaiian Islands.

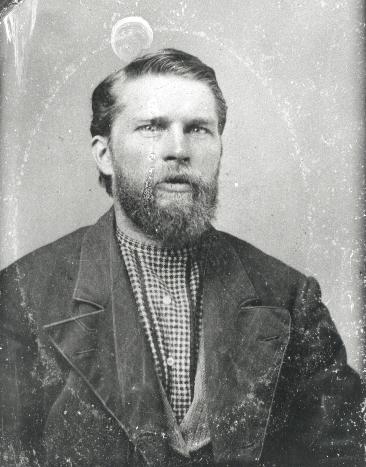

One of the crew on the "May Dacre" was the young adventure seeker Elbridge Trask. He has been described as being nearly six feet tall, weighing two hundred muscular pounds, with deep set blue eyes and red hair.4 Osborne Russell, a companion of Elbridge, describes him as being a great easy good natured fellow but having been bred a sailor and not much of a landsman, woodsman or hunter.5 He must have been a fast learner because in the ensuing years Elbridge survived many harrowing escapades.

Elbridge spent the summer of 1835 working with the crew of the "May Dacre" at Fort William on Sauve Island.6 September 30, 1835, he signed a contract to work for Captain Wyeth's Columbia River Fishing and Trading company as a trapper at Fort Hall. They arrived at Fort Hall on December 9, 1835. The group of new recruits was composed of sailors from the "May Dacre", Sandwich Islanders (Hawaiians) and Kanakas indians.7

Early in 1836, Captain Joseph Thing took a group of trappers from the fort south to the region of the Portneuf River.8 Here under the tutorage of experienced trappers and hunters, Elbridge and the other greenhorns learned hunting and trapping skills. Jo Tuthill describes Elbridge as a " quiet young man, given to listening and staying in the background, while the more boisterous trappers spun their half truths around the campfire at night in the long winter days and nights at the camp ".9

The trappers returned to Fort Hall and received their discharge from Captain Wyeth's company during the summer of 1836. Jo Tuthill says Elbridge joined the American Fur Company under the command of Andrew Dripps. If Elbridge joined with Dripps company of trappers, he most likely joined them at the 1836 fur trappers rendezvous which was to begin July 1 at the mouth of Horse Creek on the Green River. Wyeth had arrived on the first with a small party of men and it is likely that Elbridge was in that group.

The 1836 rendezvous was unusual because the supply train of the American Fur Company brought with it from Missouri the first two white women to come over trail to the Oregon Country. Narcissa Whitman, the recent bride of missionary Doctor Marcus Whitman and Eliza Spalding, The wife of Reverend Henry Hart Spalding.10 Also with the supply caravan from Missouri was the Scottish nobleman Captain William Drummond Stewart. The caravan had been given a Rocky Mountain welcome two days before arriving at the rendezvous site by a group of trappers and indians, who had heard that white women were in the group. The welcoming party had come charging up to the train firing their rifles over the caravans heads and giving out with blood curdling screams and war hoops.11

Where Elbridge Trask spent the fall of 1836 and the spring of 1837 is not known because the travels of Andrew Dripps and his trappers have not been documented. The historians Dale Morgan and Eleanor Harris have speculated that Dripps trapped the Snake River during the spring hunt of 1837.

Elbridge probably attended the fur rendezvous of 1837, located again on the Green River at the mouth of Horse Creek. This rendezvous was distinguished by being the first Rocky Mountain fur fair to be documented visually. Captain William Drummond Stewart had returned and brought with him the artist Alfred Jacob Miller. Miller's paintings of the rendezvous give us our only visual images of the famous Rocky Mountain rendezvous. Perhaps Elbridge Trask is one subjects in Miller's works.

Miller also recorded with an artists eye for detail a verbal description of the scene. "The scene represented is the broad prairie; the whole plain is dotted with lodges and tents, with groups of indians surrounding them;-In the river near the foreground indians are bathing; to the left rises a bluff overlooking the plain whereon are stationed some braves and indian women. In the midst of them is Capt. Bridger in a full suit of armor. This gentleman was a famous mountain man, and we venture to say that no one has travelled here within the last 30 years without seeing or hearing of him. The suit of armor was imported from England and presented to Capt. B. by our commander;-it was a fac-simile of that worn by the English life-guards, and created a sensation when worn by him on stated occasions."12

At the 1837 rendezvous, Andrew Dripps gave over the command of the trapper brigade to Lucien Fontenelle. Dripps was to return to Saint Louis with the years harvest of furs.13 Where Elbridge Trask travelled during the 1837-1838 trapping season is documented by Kit Carson.

"We reached rendezvous at the mouth of Horse Creek on the Green River in six days. We remained here about twenty days, When McCoy went back to Fort Hall and I joined Fontenelles party bound for the Yellowstone. The party was one hundred strong-fifty trappers and fifty camp-keepers. We had met with so much opposition from the Blackfeet that this time, as we were in force, we determined to trap wherever we pleased, even if we had to fight for the right."

"We trapped the Yellowstone, Otter, and Musselshell rivers and then went up the Big Horn and on to the Powder River, where we wintered." "We remained in our camp on Powder River till the first of April, 1838. The time passed pleasantly, but it was one of the coldest winters I have experienced. We had to keep our animals in a corral for fear of losing them. Their feed was cottonwood bark, which we pull from the trees and thaw out by the fire."

"We had to keep the buffalo from our camp by building large fires in the bottoms. They came in such large droves that our horses were in danger of being killed when we turned them out to eat the branches of the trees we cut down."

"We now commenced our hunt, trapping the same streams we had trapped in the fall. We traveled to the Yellowstone and up the Twenty-Five-Yard River to the Three Forks of the Missouri, and then up the North Fork of the Missouri." "We continued up the North Fork of the Missouri to the head of the Green River where an express overtook us with the news that the annual rendezvous would be held on the Wind River. We set out for that place and arrived in eight days."14

Osborne Russell, Who had joined Fontenelle's Trapping party at their winter quarters on the Powder River, gave a description of trapper's equipment in the party. "A trappers equipments in such cases is generally one animal upon which is placed one or two Epishemores a riding saddle and bridle a sack containing six beaver traps a blanket with an extra pair of mocasins his powder horn and bullet pouch with a belt to which is attached a butcher knife a small wooden box containing bait for beaver a tobacco sack with a pipe and implements for making fire with sometimes a hatchet fastened to the pommel of his saddle his personal dress is a flannel or cotton shirt (if he is fortunate enough to obtain one, if not Antelope skin answers the purpose of over and under shirt) a pair of leather breeches with Blanket of smoked Buffaloe skin, leggings a coat made of Blanket or Buffaloe robe a hat or cap of wool, Buffaloe or Otter skin, his hose are pieces of blanket lapped around his feet which are covered with a pair of moccasins made of Dressed Deer Elk or Buffaloe skins with his long hair falling loosely over his shoulders completes his uniform. He then mounts and places his rifle before him on his saddle."15 This description gives us a general idea of how Elbridge Trask might have appeared if we could have seen him in 1837.

It was in 1838 after joining trapping brigade of Fontenelle, with Jim Bridger as pilot, that Osborne Russell begins to refer in his journal to his old comrade on March 30, 1839 as being Elbridge Trask.16

Osborne Russell and Elbridge had gone to the Green River thinking the summer renzdevous was being held there only to find a note stuck on the wall of an old log cabin used to store supplies at the past rendezvous. The note said the whites were to be found at the Forks of the Wind River.17 This was not good news to Osborne and Elbridge as their animals were fatigued. The two crossed around the south end of the Wind River range to the south flowing fork of the Wind River which is known as the Popo Agie River.

The 1838 rendezvous was held on the Popo Agie River just upstream from where it joins with the Wind River to form the River known as the Big Horn River. Andrew Dripps had brought the supply train from Saint Louis that year. Sir William Drummond Steward was with the train for the last time since his older brother had died and Steward had inherited the family title and estates and now must return home to assume the burdens the title brought with it.18

Andrew Dripps and Jim Bridger were to take the trapping brigade out for the 1838-39 trapping season. The main question on every ones mind when the 1838 renzdevous came to an end was whether there would be a renzdevous in 1839. The number of beaver pelts the trappers had brought to the 1838 renzdevous was substantially less than had been brought in during previous years. Pierre Chouteau, head of the company, was wondering if it was worth the effort to sent a supply train in 1839.

Osborne Russell and Elbridge Trask left the renzdevous site on the 20th of July with 30 trappers. They travelled up the Wind River. Elbridge and Osborne left the main body of trappers and crossed southward over a high ridge into the valley of the Gros Ventre Fork of the Snake River. They travelled down the Gros Ventre Fork about 20 miles and crossed over a ridge to the north and into the valley of a stream flowing into the Snake River about 10 miles below Jackson Lake. They trapped here until July 29th and then crossed back over the ridge to the Gros Ventre where they found Dripps and Bridger with about sixty men.19

Osborne and Elbridge left the main party again and picked up their traps over the ridge to the north. They then travelled to the west and across the Tetons to the Henry's Fork River. They trapped for several days and found the main party on the Middle Fork of the Henry's. The Henry's Fork River is named after Andrew Henry, who was a partner in the Saint Louis Missouri Fur Company. The Missouri Fur company was organized 1808. Andrew Henry was chosen to take a party up the Missouri to the Three Forks. After much trouble with the Blackfeet, Henry had crossed from the Three Forks of the Missouri over a pass to a lake and river to the south. In 1811, Henry built what was to be the first American post west of the Rockies on the Stream that bears his name.20

On August 11th, the day after they had joined the main camp, Elbridge and Osborne were off again to trap the stream they had just left. They trapped the Henry's fork region until September 7th when they began travelling down the river toward Fort Hall. They stayed at Fort Hall until the 20th of September. From then until October 5th, they trapped the Raft River with ten other men. On October 18th they started with six men to hunt buffalo for winter meat. By late November the weather had become cold and the snow was fifteen inches deep. Returning to the fort, they stayed there until January 1st.

They had become tired of dried meat and decided to travel with four other men to where the Lewis Fork leaves the mountains. There they planned to spend the rest of the winter killing and eating mountain sheep. They arrived at their destination on the 20th of January having been followed there by seven lodges of Snake Indians. Here they found plenty of meat in the form of mountain sheep, elk and buffalo. They also found some open water in beaver ponds and were able to take some in their traps.

On March 18th the winter weather began to break so Elbridge, Osborne and two Canadians began to move up the river to begin the spring hunt. They traveled over the mountains to the head of Gray's Creek. There the two Canadians left them and Elbridge and Osborne trapped the headwaters of Gray's Creek until April 25th. Travelling to the head of Gray's Marsh, they cached their furs on May 2nd. Needing salt to preserve their furs they travelled to a salt spring on the headwaters of the Salt River to the east. Here they found twelve of their former trapping companions who were also after salt. Elbridge and Osborne remained there two nights and left to go back to Gray's Marsh. Picking up their fur they returned to Fort Hall on the 5th of June.21 The fort now belonged to the Hudson's Bay Company.

They remained at the fort until June 26th when they left with a Missourian named White and a French Canadian to trap the Yellowstone and Wind River Mountains. They spent the forth of July at the outlet of Jackson Lake. Osborne caught twenty trout which they ate with buffalo meat and coffee for their Independence day feast. Travelling up the east side of the lake they followed the Lewis Fork to Lewis Lake where they camped on July 9th. Going along the west side of the lake they came to Shoshone Lake. The next day they travelled along the Shoshone Lake to the northwest side where they encountered the Shoshone Geyser Basin. After spending several hours observing the thermal activities they travelled north a few miles to the Firehole River. They spent the next few days trapping the Old Faithful region. After marvelling over the thermal features they travelled on July 16th down the east side of the Firehole River to the Gibbon River which they followed eastward. Leaving the Gibbon they travelled southward to Hayden Valley on July 18th.

The four men followed the Yellowstone River from Hayden Valley to where it leaves Yellowstone Lake. They made camp at the outlet of the lake. Remaining there they trapped the beaver streams in the region. July 28th they travelled to what they called "Secluded Valley" and what is known today as Lamar Valley. They remained in this region trapping the headwaters of Pebble Creek until August 9th. Leaving Lamar Valley they travelled northwest across the mountains until they reached the Yellowstone River where they travelled north along the Yellowstone until they had reached a point near the open plains.

Some of the party insisted on going out onto the plains to hunt buffalo. Osborne was against this as he thought it was too dangerous to run the buffalo out in the open where the Blackfeet might notice the commotion. The men returned that night with buffalo meat and the information that a village of 300 to 400 lodges had left the river a couple of days earlier. Crossing the Yellowstone they followed the river to the mouth of The Gardner River which they followed southward to an open valley known as Gardner's hole.

Returning southeastward across the ridges they returned to Lamar Valley on August 26th. The next day they travelled to the outlet of Yellowstone Lake and set up camp on Pelican Creek just upstream from where the Highway crosses Pelican Creek today. Elbridge left camp with the Canadian trapper to hunt while Osborne and White were left in camp alone. They were camped on a bench about twenty feet high on the southeast side of Pelican Creek. This bench runs parallel to Pelican Creek and is covered with pines. While White slept, Russell went to a spot about thirty or forty feet from where they were sleeping to cut some meat from some they had drying in the sun. He pulled off his powder horn and bullet pouch and laid them on a log. After eating, Osborne made a fire and sat down to smoke. The area behind the camp was thick with down timber. Looking out into the open meadow near the creek Russell checked on the grazing horses. To his astonishment he saw the heads of some Blackfeet slipping along below the edge of the bench and within thirty steps of him. Jumping for his rifle he awakened White. Looking for his powder horn and bullet pouch he saw that they were already in the hands of one of the indians. The indians now had Russell and White completely surrounded. Cocking their rifles they boldly started for the woods behind the camp.

The Blackfeet stepped back and opened up a path about twenty feet wide. Russell and White plunged through this gauntlet of screaming Blackfeet. After running only a few steps White took an arrow in the right hip. Instantly afterwards Osborne also was hit by an arrow in his right hip. Both men continued to run for the down timber behind the camp. In a few more leaps, Russell took another arrow in the right leg above the knee. This caused him to fall on his chest across a log. The indian who has shot him in the leg was only eight feet away and sprung at Russell with an uplifted war axe. Osborne rolled to the side and avoided the blow. Hopping from log to log the two trappers moved through a hail of arrows from the surrounding Blackfeet. After moving about ten paces beyond the indians, White and Russell turned and took aim at the braves. This action made the Blackfeet duck behind the trees and begin firing their rifles at the beleaguered trappers. Running and hopping another fifty yards into the down timber, Russell and White made a stand behind some thick logs. Determined to die like men, they aimed their rifles across the top of the logs to where the indians would appear. They determined to kill the first two blackfeet whenever they turned their eyes toward the trappers. The Blackfeet came into view and splitting into two files passed on either side of the pile of logs the trappers were in without ever seeing the lucky men. Passing on into the woods behind the trappers the forty to fifty indians disappeared into the trees.

After the sound of the indians died away Russell and White hobbled toward the lake. Russell who had lost a lot of blood, moved very slowly and became very thirsty from the blood loss. Reaching the lake, Osborne crawled to the water from the trees and brought back some water in his hat. White became very depressed over their plight and despaired that they were going to die. Russell who was the older, convinced White that all was not lost and they could survive.

Covering themselves with leaves and needles they spent the night in the covering shelter of the trees. On awaking in the morning, Russell was so stiff from his wounds that he could not stand with out Whites help. Using a couple of sticks for crutches, Russell hobbled with White to a thick grove of pines. They had only entered the protection of the pines, when they heard indians talking and singing. In a few moments sixty Blackfeet passed near the grove where the two trappers were hiding. Sighting some elk swimming in the lake, the indians began firing on the animals killing several. Dragging the elk ashore, the indians proceeded to butcher the elk in full view of the trappers. The indians remained near the grove for three hours while they butchered and packed the meat. Moving up the shore of the lake about a mile, the indians camped.

Leaving their hiding place in the pine grove, Russell and White made their way back toward their camp site on Pelican Creek. Keeping in the thick timber, they slowly made their way with White carrying Osborne's rifle. Reaching the camp site they found the Canadian trapper searching around in the trees.

Inquiring where Elbridge was, the Canadian told them that he and Elbridge had returned to camp the evening before and the indians had pursued them into the wood where he and Elbridge had separated. He had not seen Elbridge since then. Looking about to see what the Blackfeet had left, all they could find was a bag of salt. The indians had taken their horses, furs and all their gear.

Leaving a message on a tree telling Elbridge which directions they were going, they walked down to the shore of the lake and began following the shore toward the west. They stopped for the night and built a fort of logs to shield themselves from the cold wind. During the night their fire set the trees on fire and they had to move to a different site. Reaching the Yellowstone River they made a raft of logs and crossed to the other side. There they build a fire and rested for the day, hoping that Elbridge would see their smoke and find them.

Osborne bathed his wounds in salt water and made a salve of beaver's oil and castoreum. This eased the pain and took out some of the swelling but he was still very stiff. Travelling down the west side of Yellowstone Lake, they camped at some hot springs where they killed an elk. This was probably the West Thumb Geyser Basin. Having no blankets and very few clothes they spent a miserable night freezing on one side and buring from the hot fire on the other.

Leaving the lake at the hot springs they travelled south to Heart Lake. One of the hunters had killed a deer and Osborne wrapped the skin around himself and managed to sleep more than four hours. This refreshed Osborne and they walked around the east side of Heart Lake and travelling over some very rough hills camped at the forks of the Lewis Fork River where they had followed the west fork to Lewis Lake on July 9th.22

They were over one hundred miles from Fort Hall and they presumed that Elbridge was dead. Moving down the Lewis Fork to Jackson Lake, they travelled along the west side of the Lake and crossed over a pass to the Henry's Fork. Passing down the Henry's Fork they reached the Snake River on September 4th. Travelling with out eating they reached Fort Hall in two days. At the fort, Osborne made a quick recovery and was out trapping beaver again ten days later.

On September 13th, Elbridge arrived at the fort. Not knowing the country they were in when attacked by the Blackfeet, he had wandered for several days until he came upon the trail they had followed in the summer. Following this trail which he was familiar with he found his way back to the fort alone. His woodsman skills must have improved considerably from what they had been in March when Osborne had evaluated him as being more of a sailor than a woodsman.

On October 20th, Elbridge and Osborne joined a party of fifteen men who left Fort Hall to travel to the Jefferson Fork of the Missouri to kill buffalo for winter meat. Returning to the forks of the Snake River, the hunting party planned to spend the winter there. Elbridge, Osborne, White and Alfred Shutes decided to return and spend the winter near the fort.

Pitching their leather tepee in a cottonwood grove near the fort, they turned their horses loose to care for themselves. Since the men had enough meat and provisions to last until spring, they had nothing to do but gather firewood and amuse themselves. Elbridge, Osborne, White and Alfred Shutes spent the winter in their snug lodge reading books from the Hudson's Bay Company's library a Fort Hall.23 The books they read included works by Byron, Shakespeare, Scott, the bible and Clark's commentary on the bible. They also read works on chemistry, geology and philosophy. A fur trappers University of the Rockies.

The winter was mild with very little snow and on March 10, 1840, Elbridge and Osborne set out for their old spring trapping grounds at Gray's Marsh. Finding a spot bare of snow on a south facing slope they set up camp. The snow in the valley was three feet deep and they soon suffered from snow blindness.

At this point, Elbridge and Osborne had a disagreement about what to do. Elbridge wanted to travel the Salt Fork to kill some buffalo and Osborne felt that the streams were too high to cross.

The men parted company on May 20th. Elbridge packed his horses and set out to hunt buffalo on the Salt Fork. Osborne's

fear of high water turned out to be correct as Elbridge lost his traps while crossing the Gray's River.

Soon after losing his traps in the Gray's River, Elbridge met another hunting party and returned to Fort Hall with them on June 15th. Elbridge found Osborne at the fort. He tried to get Osborne to join with him and some other men to hunt the Yellowstone Mountains. Osborne, who was still irritated about Elbridge leaving to hunt buffalo on the Salt Fork, declined the invitation. Elbridge must have returned to the Yellowstone country for the summer of 1840.

The rendezvous of 1840 was again held on the Green River. The fur trade had declined so much that this was the last time that a supply train brought supplies from Saint Louis. It seems likely that Elbridge would have attended this last rendezvous since he had not missed one since coming to the mountains.

In September of 1841 Elbridge, Osborne and Alfred Shutes again set out together to hunt. The hunted in the region of the Soda Springs on the Bear River and then travelled to the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Returning to Fort Hall in November.

Remaining at the fort only a few days, they set out to trap the headwaters of the Portneuf until the freeze up. Russell noted in his journals, "it was time for the white man to leave the mountains as beaver and game had nearly disappeared".24 If this loss of game was a problem to the continuation of free life as the trappers had lived it, it was a total tragedy for the misfortunate indians who did not have the alternatives the white men had. Elbridge, Osborne and Alfred spent the winter at Fort Hall again. The winter of 1841-42 was unusually cold and snowy.

In June a party from the Columbia River arrived at the fort on their way to the United States. Alfred Shutes, who was homesick for his native Vermont decided to travel with the party to return to his home. Elbridge and Osborne also decided to give up the free mountain life and settle down in the Oregon country.

On August 22, 1842, Elbridge and Osborne joined a wagon train led by Dr. Elijah White that was bound for the Willamette Valley in the Oregon country.25 On the wagon train to Oregon was Hannah Able, a young widow from Indiana with a baby daughter. She was travelling with the W. T. Perry wagon. Not having been around any single, young, white women in years, Elbridge was taken by Hannah's charms. On arriving at Willamette falls, Elbridge married Hannah on October 20, 1842.26

Elbridge and Hannah took up residence on the Clatsop Plains near Astoria. They built a house near Solomon Smith, an old trapping companion. The were considered by their neighbors to be of the best type of pioneer families. When the pioneers were in need of cash a few years later, Elbridge and a group of neighbors decided to build a ship, fill it with produce and sail it San Francisco in 1848. They named the ship the Pioneer. This venture provided cash to buy some of the things the settlers needed.27

In 1852, Elbridge and Hannah decided to leave the Clatsop Plains and settle in the Tillamook country to the south. Elbridge and Hannah were the first family to settle in this wild but beautiful country. A historical novel was written about Elbridge and Hannah's experiences by Don Berry.28 Elbridge and Hannah settled on the river that now bears his name, the Trask River.

In 1855, the settlers built a ship which they christened the "Morning Star".29 Don Berry also wrote a historical novel about the building of the "Morning Star".30 Elbridge continued to be actively involved in the settlers activities serving as Justice of Peace and County Commissioner. His home served as the communities main meeting place in the early days. When the Tillamook Indians became upset, Trask build a fort at his home for the settlers to take refuge in.31 Elbridge and his son-in-law Warren Vaughn negotiated with the Chief of the Tillamooks and the trouble died down.

Elbridge's seafaring days were not over as he served as the Captain of a vessel named the "Gull" on several voyages to bring supplies to Tillamook.32 He also began to build his own schooner on the first of May, 1855. The schooner was launched May 8, 1858. Elbridge named the schooner after his daughter Rosaltha.33

On October 8, 1858, Elbridge's daughter Harriet married Warren N. Vaughn. They were married by the Justice of the Peace as there were no preachers in the Tillamook settlement.34

Elbridge's health was becoming increasing poor. He even had to hire a sea captain to run his ship as he was no longer able to do this himself. The man he hired to captain his ship did such a poor job that the ship had to sold in San Francisco to pay off the debts that had built up.

Elbridge's health continued to decline and he died at the age of forty-nine on June 22, 1863. He told Hannah he wanted to be buried on a hill top near his home. He left the following children; Rosealthe Able Tripp - the baby daughter Hannah had with her on the wagon train when Elbridge first met her, Harriet and Martha -twins born on the Clatsop Plains, Nancy, Jane, George, Eodora, Charles, William and Avilla.

Elbridge Trask, the sailor from Massachusetts, mountain man, trapper, adventurer and pioneer had lived an exciting, rich life. He saw the true old west before the image was distorted by the Hollywood writers of the twentieth century.

1 Beverly, Mass. Vital Records, data added to this story by R.W. Trask

2 James Duncan Phillips, Salem In The Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, Mass. 1933), p. 41.

3 Sampson, William R. "Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth." In The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, ed. Leroy R. Hafen, vol. 5, pp. 381-401. Glendale, Calif.

4 Tuthill, Jo "Elbridge Trask." In The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, ed. Leroy R. Hafen, vol. 4, pp.369-381. Glendale, Calif.

5 Russell, Osborne, Journal Of A Trapper, p. 96. Lincoln, Nebraska : University of Nebraska Press. 1965.

6 Tuthill, The Mountain and the Fur Trade of the Far West, vol. 4. p. 370.

7 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, p. 39.

8 Tuthill, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, vol. 4, p.371.

9 Ibid, p. 371.

10 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, p. 41.

11 Gray, William H., A History of Oregon, 1792-18947, (Portland: Harris, Holman) 1870, pp. 118-19.

12 Ross, Marvin C., ed., The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, Norman, Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press, 1951. p.159.

13 Carter, Harvey L. "Andrew Drips" In The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, ed. Leroy R. Hafen, vol. 8, pp.144-156. Glendale, Calif.

14 Carson, Kit, Kit Carson's Autobiography, ed. Milo Milton Quaife, pp.47-52. Lincoln, Nebraska; University of Nebraska Press. 1966.

15 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, pp.82-83.

16 Ibid, p. 96.

17 Ibid, p. 90.

18 Porter, Mae Reed and Davenport, Odessa, Scotsman in Buckskins, Hastings House, 1963. P. 172.

19 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, p. 91.

20 Trask, Juel M., Andrew Henry, from a paper presented to the Colorado Fur Trade Historical Society, February, 1983.

21 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, p. 97.

22 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, pp. 101-107.

23 Tuthill, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, vol. 4, p. 376.

24 Russell, Journal of a Trapper, p. 123.

25 Ibid, p. 125.

26 Tuthill, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, vol. 4, p. 377

27 Ibid, p. 378.

28 Berry, Don, Trask, Viking Press, Inc. 1960.

29 Vaughn, Warren N., Early History of Tillamook, unpublished manuscript, p. 54.

30 Berry, Don, To Build A Ship, Popular Library, N.Y., 1963.

31 Vaughn, Early History Of Tillamook, p. 69.

32 Ibid, p. 71.

33 Ibid, p. 78.

34 Ibid, p. 79.

Return

Return

rwtrask@rcn.com

rwtrask@rcn.com